WALKING TOWARDS GATE NO. 85 & 86

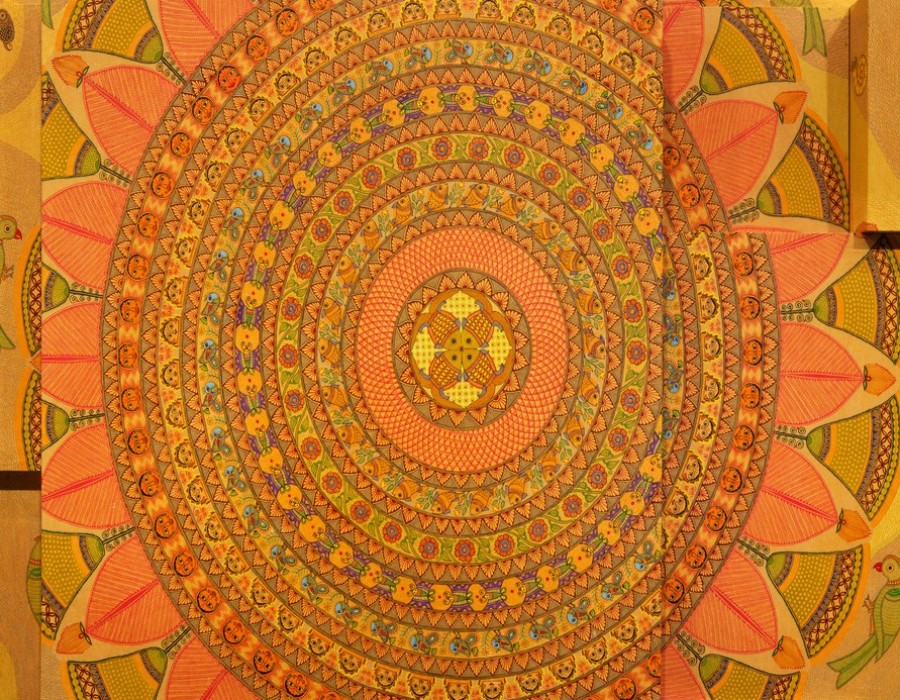

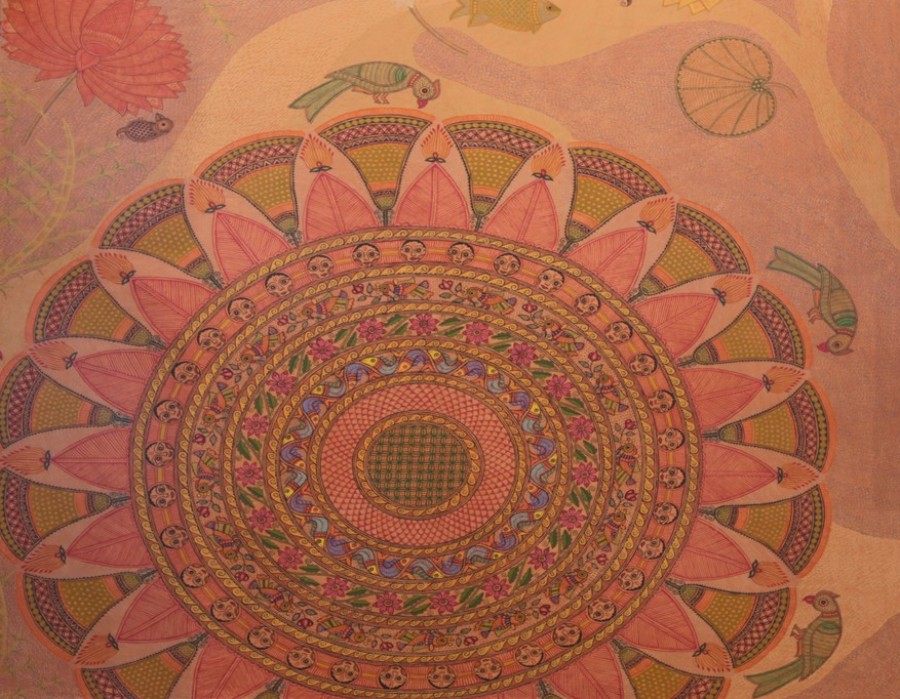

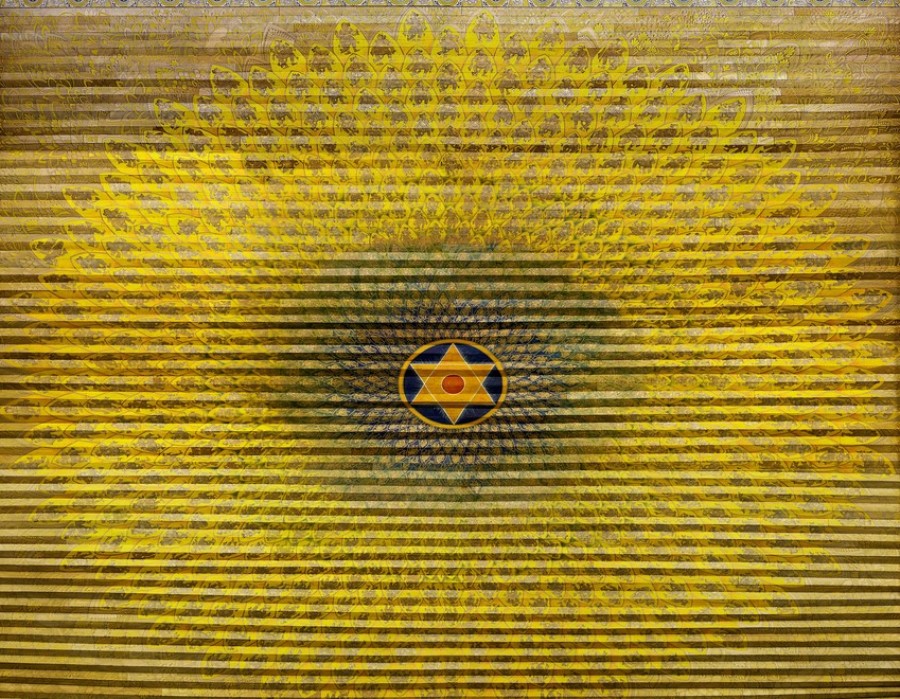

‘India Greets’ is designed as a tableau of India as one of the first installations which visitors encounter as a welcoming gesture to The Artbeat of New India Museum is a densely populated vista of diverse traditional doorways, facades, faces and fascias.

Sourced from across the country, they are a language of motifs, designs, and traditional crafts skills. They together offer a testament to cultural diversity of India as well as the often intangible commonalities that transcend ethnicity, religious affiliations, and geography. These are replete with symbols of welcome and protection – lotuses, sacred geometries, angels, ancestral figures, and celestial guardian figures.

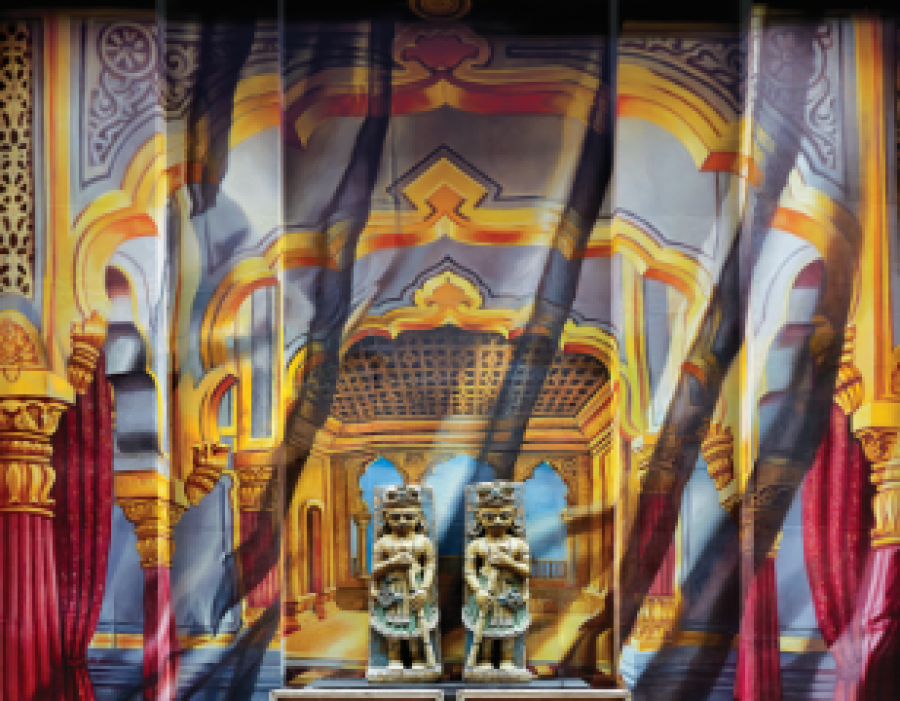

THEATRICAL SCREENING

ANIL NAIK AND MORESHWAR PATIL

In rendering the artwork thus, Patil and Naik draw on the late 19th and early 20th century painted sceneries which were hung as backdrops in theatres and photography studios. Painted by both well-known and anonymous painters, these curtains transformed prosceniums into vividly coloured forests and riversides, village streets and bustling town squares, as well as gardens, royal courts and sumptuous palaces.

Adopted by theatre troupes in a number of Indian cities, especially in Maharashtra, West Bengal and Karnataka, the curtains were painted on cotton, and described the locale of scenes summoned by the narrative, demarcated the background from the foreground and accommodated the actors within realistically rendered sceneries. The art of the painted curtains evolved into elaborate spectacles in the Parsi and Marathi theatre traditions.

“The theatre curtains used in drama and early films in the era before hoarding technologies existed were painted by hand. In many instances, the artists were not formally trained but had learnt through a process of apprenticeship from the previous generation of theatre curtain painters,” says Anil Naik.

“We had to suspend our critical analysis and embrace their language, taking care to ensure we retained the style of every individual atelier. Thus when reproducing theatre curtains that exhibited a magical realism, we would use perspective to create the illusion of a three-dimensional space. In others, where a table is shown with four legs when in reality only two would have been visible, we retain the unrealistic perspective.”

Band-like sections of the enormous installation can be viewed from each successive storey of the airport and in some instances; the painted curtains can be viewed as an entire elevation. Overseeing twenty artists, Naik and Patil drew upon their experience as teachers at the JJ School of Art.

Making the painted backdrop to appear creased, as though actually suspended from battens as in the proscenium theatre, proved troublesome. “After five months of explorations, we decided to paste the canvas flat on the wall and to distort the painted sceneries to simulate the folds of the curtains,” says Naik.

The eight-foot high narrative painting of the fabled Raja Harishchandra, composed using images from the first silent film made in India, directed and produced by Dadasaheb Phalke in 1913, is interwoven with images of contemporary Hindi Cinema. The idea here, according to Anil Naik, who painted this section, “is to combine historical drama and contemporary cinema, to explore their relationship with one another artistically.”

The artists also had to adapt to site realities, shaping the curtains to make way for functional doors, elevators and artefacts. Tangible material history, thus became another, three-dimensional layer in the montage.