ARRIVAL CORRIDOR

Art works, under the theme of ‘Layered Narratives’ flank on one side of the wall along the travelators, the moving walkways, in the Arrival corridor of T2. These specially commissioned artworks of over more than 25 of the contemporary Indian artists, some of them known and some yet to be known, give the visitors a snapshot experience of the Indian city that they are about to enter. Installations, executed in varied materials and surfaces besides wood, glass and paint include trans-disciplinary medium, recycled materials to create some static and some kinetic artworks to bring out the various shades of tangible and intangible aspects of this living entity which the city of Mumbai almost is.

Intended as an introduction to Mumbai and by extension the generic city that exists everywhere, they were conceived to reveal the fluid nature of India’s evolving urbanism. Persistent physical and emotional scapes, varying aspirations and apprehensions, dynamic perceptions and technologies, narrowed down the art-craft divide while making the old and new seamless.

WHERE’S THE PARTY TONIGHT?

ALEXIS KERSEY

Alexis Kersey’s title "Where’s the party tonight?” alludes to the energy of Mumbai, where life never stops. In a smile-inducing tableau, he combines the cosmopolitan spirit of the city and its accepting ways of assimilation. An immigrant looking for a better future or a returning emigrant looking for the omnipresent party, Kersey makes place for them, in this tight, narrative squeeze.

“The idea of the party came about from living in Goa” says Kersey. “Goa has become a party destination with a very international vibe and all these guys who had migrated overseas are returning to India because this is where the party is at!” Raised in England, Kersey returned to India in his late teens, and combines Western and Indian sensibility in his work. Inspired most by popular culture, he melds it with traditional craft techniques.

He alludes to the ‘business’ that drives the party by using pinstriped fabric fashioned into clouds at one end of the panel. This is the stage for his party, where in a world of globalized fashion trends he presents a punk rocker replete with tongue, ear, lip and eyebrow piercings, a Mohawk hairdo and a cheeky expression, yet one who has a distinct Indian identity – gold and diamond bali rings festoon the face. “I wanted to have a figure that represented this sense of self, of modernity.”

A DJ continuously spins the music, youngsters (drawn in the mode of popular children’s books illustrations) cavort around as successful Indians from overseas, dressed in costume particular to their adopted country, return to the inclusiveness of an India taking its place in a globalized world.

At the centre of the panel lies the city itself. A soaring, burdgeoning mass of towers, in a never-ending rise to the stars. Using the traditional marquetry technique, various hues of inlay add texture to this multilayered narrative. With reflective plastics, steel, aluminium, brass and copper, Kersey gives existing craft techniques a sense of contemporaneity, capturing the ubiquitous landscape that these shiny new towers currently populate our city skylines with.

\LANDSCAPE RE-MADE

VIBHA GALHOTRA

The first thing that strikes a viewer, about Vibha Galhotra's large tapestries of a city's landscape, is the material. Hundreds of different shades of ghungroos or anklet bells are stitched on to canvases: graded from light to dark, silver to gold, the clusters of ghungroos create tonalities, depth, perspective and demarcation, in what is otherwise a flat tapestry.

The work is in no way decorative or feminine. It is a reflection on the nature of our times, a way of mapping the changes we see around us. The concrete urbanscapes, quintessentially man-made, are rendered in a medium that still retains a sense of an older civilization and organicity. I wanted to reflect on this new unimagined world and the relationships it spawns," she says, with an ambiguous mix of optimism and fatalism.

"I call these works 'remade landscapes' as they are as much about deconstruction as they are about construction." According to Galhotra, making an urban landscape that resembles Mumbai came with its own set of challenges. "Since I live and work in Delhi, I can't help but view Mumbai from an outsider's perspective. My intention was not to represent Mumbai per se but to create a generic city, tapping the haphazard urban development one sees in contemporary Mumbai as well as other Indian cities." Galhotra uses elements, such as the ubiquitous earth-mover and the cranes, that tower over the shanty-like structures of clapboard houses, almost like punctuation marks in an unending sea of tiny houses that appear to grow one into the other. Humans, who build and inhabit this maze of concrete clapboard houses, are almost spectral elements, counterpoints to the massive earth-movers and cranes that dominate the composition. "To me the cranes and earth-movers are like living creatures-little monsters," says the artist, whose large inflatable earth mover titled 'Neo Monster' (2011), was shown at shopping malls, northern suburbs in New Delhi and at the Colombo Biennale.

SILENT WAYS

DILIP CHOBISA

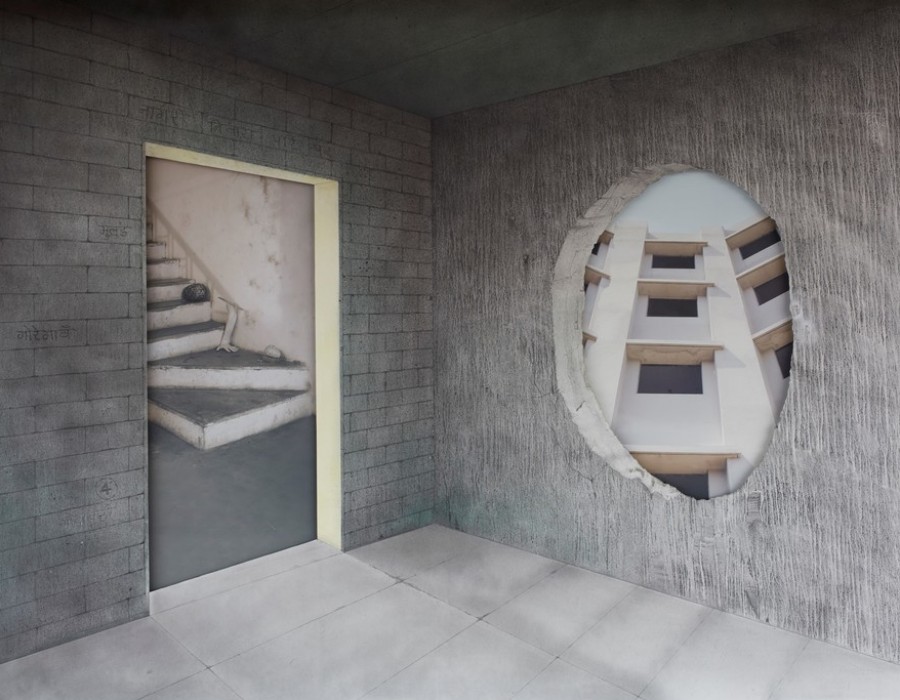

In the hustle and bustle of an airport that never sleeps, Dilip Chobisa’s work offers the viewer a few moments of silent refuge. Chobisa’s artworks offer the viewer a meticulously detailed interior ‘magical’ world where each object and scene, however mundane, is endowed with poetic meaning.

"I felt it would be very superficial to just use the usual popular symbols of Mumbai that are easy to identify. I decided to create a personal narrative from my personal experience of Mumbai," says Chobisa, who had lived in Goregaon for a year at the start of his career. He brings home the stark reality of the loneliness an outsider feels, even in a teeming metropolis bursting with 16 million people. "'Silent Ways' tries to reconstruct this sense of loneliness and isolation that I felt, with empty rooms, windows and doors that open on to empty vistas of semi urban landscapes. The windows also open onto concrete jungles of high-rise buildings and aerial views of the city as if viewed from an airplane, obliquely referencing the theme of flight."Using graphite on paper, the biggest challenge Chobisa faced was adapting his technique to the scale – the work spans 40 x 6.5 feet. "I have not worked on this scale before and creating the framework for the paper drawings meant working with a team of ten to twelve people. The entire composition was split into five paper panels of varying sizes, each mounted on fire-resistant board to enhance durability. The panels were then joined with copper and bronze rivets."Five different mise-en-scenes, conjoined here, disorient the viewer, much like the scene shifting that is going on with the city’s architecture. His almost monochromatic settings throw the varied architectural styles into strong contrast; the views through the windows are equally diverse – skyrises, distant hills, an aerial view – one’s eye

COLLECTIVE NOUNS

MANJUNATH KAMATH

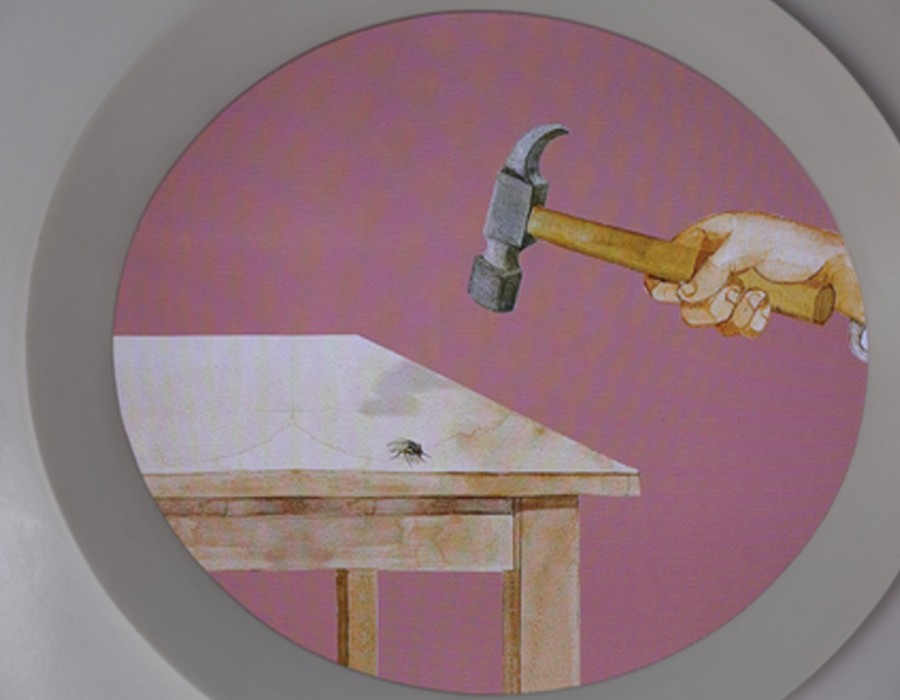

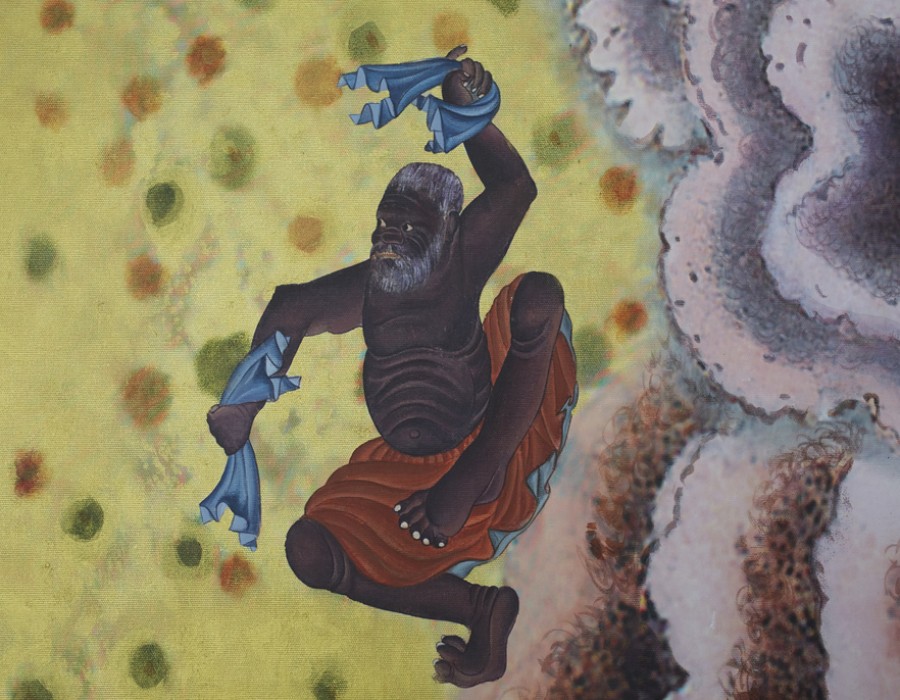

Manjunath Kamath would be happy if you were too tired to pull out your camera to take a picture of his work.

"Nowadays, people are obsessed with a different kind of imagery. When they go to a museum or a historical site, I often notice that rather than interacting with the work of art, they are busy taking pictures of it with their mobiles and cameras they miss out on enjoying the actual artwork in the here and now of the moment," observes the artist.

This becomes important in the context of his influences - Kamath sits surrounded by various keepsakes that include traditional portable wooden temples, sculptures of Lord Jagannath, voluptuous yakshi figures and popular kitschy objects like toy action figures and tinsel covered dolls. "My grandmother would narrate mythological stories to us and I would spend hours imagining the visuals in my head. The stories were not realistic but fantastical and in many ways these form the bedrock of the imagery in my work."

Inspired by the fables of the Panchatantra and Jataka Tales, Kamath's work is simultaneously humorous and serious. With his tongue planted firmly in his cheek, he quotes images from across history and everyday life (Russian storybooks, patachitra paintings, studies in art, sculpture, design and illustration), placing them in fantastical and, in some instances, absurd conditions. These painted images, as well as the accompanying animated video works, each frame hand illustrated by the artist, are mounted on oval frames, emulating traditional ganjifas (playing cards) of various sizes. The animation is so slow in certain frames that one could blink and miss it.

"In a public art project such as this, it is critical that the audience relate to the imagery and so I have deliberately chosen familiar everyday images," he says.

So, a series of paintings depict a monkey holding its own tail, the mythological image of the boar Varaha bearing the globe, a man trying on sanyogichappals (wooden clogs) while stepping on a balloon, and a faceless British Royal. Everyday did he say?

Like his paintings, the video works are also humorous. For instance, a pigeon and an egg are shown perched on fan blades, facing each other. The delicate balance of the bird and the egg gets shifted every time the bird moves and the 'helpless' egg wobbles the balancing act that is life, a reminder, that every action taken by an individual has an opposite and equal reaction.

There is no specific narrative though. Through repetition of motifs, linkages are carefully orchestrated following a thread from one frame to another.

TRASH, FASH, BASH

VIVAN SUNDARAM & RAJEEV SETHI

Building on his 2007 multimedia exhibition titled ‘Trash’ this new work, ‘Trash, Flash, Bash’, critically examines urbanization as a contemporary phenomenon, representing the different worlds enveloped within the ever-expanding skin of the city. Working collaboratively with waste pickers, Sundaram sorted through truckloads of garbage, reassembling them into an elaborate, fantastical city in the space of his studio.

"It was my interest to pick up trash, organize and spatial it as an imaginary city.” said the artist. “Everything that is typically thrown out was brought back and reorganized so that it both physically and pictorially produced a number of meanings.”Swathes of dirty toothbrushes, discarded plastic toys, soiled mattresses, wrinkled bottled, empty soda cans, cardboard cartons, barbed wire and an assortment of hardware accessories are transformed into a detailed model of an urbanscape that is all the more unsettlingly because it mines the familiar. “I wanted to draw attention not only to the astonishing quantities of garbage generated by the new urban middle class and elite, but also to the waste pickers who toil long hours to sort, sift and recycle as much of it as possible."

Living on the margins of the city, in shanty houses and slums, they are forever on the cusp of being dislocated, their homes bulldozed to make way for the ‘development’ of the city with its utopian misadventures. The artwork operates at multiple registers, investigating the social implications and aesthetics of urban waste, second hand goods, and global consumption, as well as prompting a reassessment of the nature of the urban experience.

The images include conventional photography, panoramas 60 feet in length created by ‘digitally stitching’ together 14 different images shot from the same perspective, and digitally constructed images that defy the laws of-physics to form disorienting mutations of aerial, frontal, profile, and macro views. Within this vivid, often disorienting, depiction of conspicuous consumption and its environmental aftermath, are cut outs framing TV screens playing segments from Sundaram’s video works,‘Turning’ and ‘Marian Husain’, as well as from a public art project titled ‘Floatage’ in which the artist floated 10,000 bottles down the River Yamuna.

"The work is essentially a texture of the visual chaos of our Indian urban cities,” says the artist. “It was not intended to be the sort of artwork that one is supposed to study. Rather, it is a total gestalt."

Cumulatively, the video sequences reveal all manner of spontaneous improvisations from waste, youth who earn a meager livelihood ‘scavenging’ recyclable wastes daily from open drains, and similar re purposing of “ industrial” materials into high fashion, as statements both ideological and political.

A TALE TO TELL

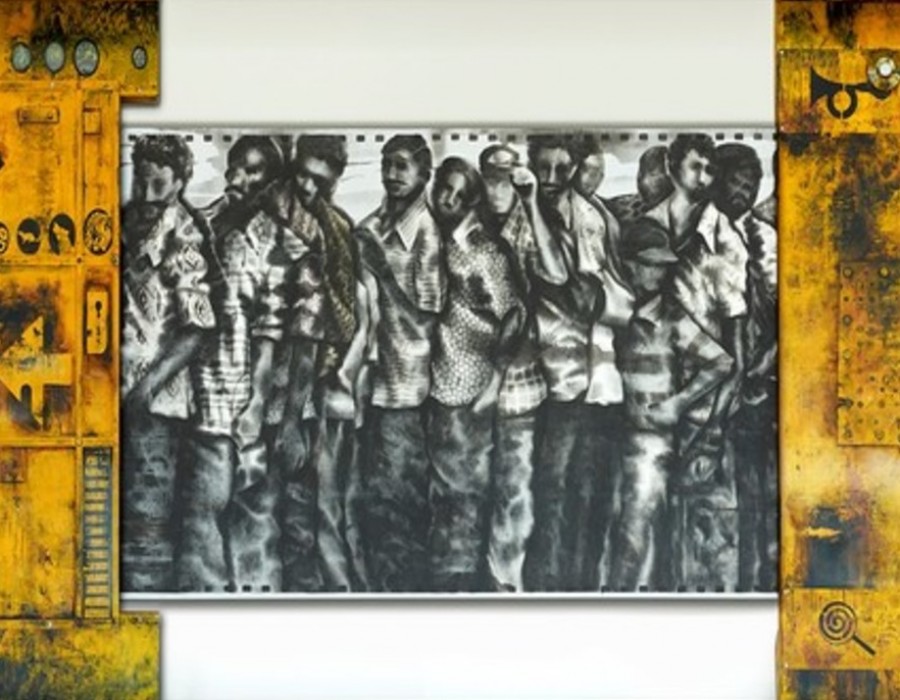

TANMOY SAMANTA

In this work, Tanmoy Samanta references the bioscope-it seems only natural to view it through this early form of a movie projector in a city that is home to Bollywood. Samanta translated the idea of the bioscope into advertising light boxes made of aluminium and mounted them on large wooden panels painted in acrylic and textured with rice paper. The box contains a scroll propelled by a motor.

Describing the challenges he faced while creating the 40 x 6 feet in size, consisting of 10 painted wooden panels artwork, Samanta said. "I usually work in small format, so the scale of the project was rather novel. I created each section individually over the span of a year, piecing them together at the end. I also had to be careful to make sure that the images of the moving scroll in the light box added to narrative created by the still images near them." The play between the still and moving images, is critical to the efficacy of the narratives. For instance, the birds in the background are close to a window in the moving image, and then suddenly, they appear to have flown away.

The concurrence of images (crawling traffic, construction sites and concrete housing) while referencing changes in the city, is a metaphor for the nature of memory, fragments of experiences, piling up year on year, some resurfacing and others fading with time. "The images and surfaces are built with layers of colour but fade into another, a bit like our memory," said the artist, whose work is as much about perception as it is about viewing. In a way, Samanta relies on his audience to complete the story, giving them only clues and hints to build on.

The work hints at the lonely mechanisms of urbanism and not at the clutter of the city. "The juxtaposition of images is often designed to dislocate the expectations of the viewer, give them the feeling that they are seeing something that isn't quite there in the image. Sometimes, it’s something sinister," says Samanta.

WINDOWS: WORLDS WITHIN

YOGESH RAWAL

Yogesh Rawal’s installation of windows and doors assembled formally, look cheerful with breaks of treated wood between his signature colourful collages. But these windows and doors once opened into the rooms of mill workers, the erstwhile immigrants who came to the city to work in the once booming cotton mills. The chawls ,or low cost housing blocks that they lived in,had rooms"measuring a mere 10 feet by 10 feet shared by 20 people. There would be a single window and a single door,"says Rawal.

With no privacy, high-density population, cramped and often unsanitary quarters, and 4-5 toilets to be shared by the inhabitants of entire floor, the chawls are testimony to the inhuman conditions that labour was expected to live and work in. Despite these adverse conditions, the migrants put down roots in the city, influencing its economy, politics and culture. Travelling from various parts of the country, they gave the city its now famous cosmopolitan character.

"The workers would live in shifts, where the first set of workers would go for work, and the second set would come to the room to rest. Most of their families lived in their native place, which was located in the Konkan and Vidarbha region of Maharashtra. These labourers are the people who have actually built this city initially, with their blood and sweat,"says Rawal.

As chawls were broken down to make way for malls, luxury apartments and commercial complexes, the windows and doors were sold to scrap vendors. It took Rawal four to six years to source the pieces used in this work."I wanted to use the original woodwork and elements rather than make new ones. The texture and feel of replicas would have been completely different. They would have completely lacked authenticity."

Papering the shutters of the windows and doors, inserting collaged panels, and louvres, Rawal has constructed a complex assemblage loaded with his iconographic symbolism. The wooden panels are treated and painted black, symbolising the worker’s bleak existence. The collaged panels are patterned in torn pieces of bright turquoise, vermillion, green and mustard yellow papers, that seem to be painted rather than glued. Coaxed into myriad shapes, these translucent forms suggest the ephemeral joys shared by the migrant labourers living together in the chawls. The louvred windows, which are automated to swing open and shut, are collaged in tissue paper and cellulose, symbols of their migrations and aspirations.

FIFTY YEARS OF INDIAN CINEMA

ALPESH GAJJAR

You've landed in the film capital of India, a city that churns out a large portion of the 800 films that are produced each year in this country. Alpesh Gajjar's billboard inspired artwork is a foretaste of what populates this city - you are never, not under the gaze of stars. Bollywood filmstars are worshipped here, as much as Gods are. Films are the opium of the masses, the escape from the harsh realities they live in.

Alpesh Gajjar belongs to a family of Bollywood billboard painters who drew inspiration from the posters of films from the West but gave them a distinct indigenous sensibility. Hand-painted in bold strokes and lurid colours, they reflected the painter's immediate surroundings and the glamorous photographic images from commercial advertisements.

Here, after deliberation, Gajjar in consultation with curator Rajeev Sethi decided to create a timeline of Bollywood milestones through iconic images of Indian cinema – the actress Nargis Dutt as 'Mother India', the smoky sepia image of Guru Dutt and Mala Sinha in 'Pyaasa', the "evergreen couple" Raj Kapoor and Nargis in a still from 'Barsaat', followed by larger than life images of stars such as Zeenath Aman, Amitabh Bachchan, Shah Rukh Khan, Madhuri Dixit, and Aamir Khan.

Six panels run 70 feet in length and 6.5 feet high. Working in a style reminiscent of his grandfather's era, Gajjar first sketched the imagery in chalk directly on the canvas. The drawing was then colour coded with the foreground and background clearly demarcated. The colours were filled in, with shading and highlights being added for additional drama. Unlike the original billboards, these images are intended to be seen close-up.That the viewers will be only two or three feet away from these images is a bit unfortunate; ideally these images should be viewed from 500 meters away," says Gajjar, yet hopes that "this work will create fresh excitement around a dying art."

REPRODUCTION BEFORE THE REVOLUTION

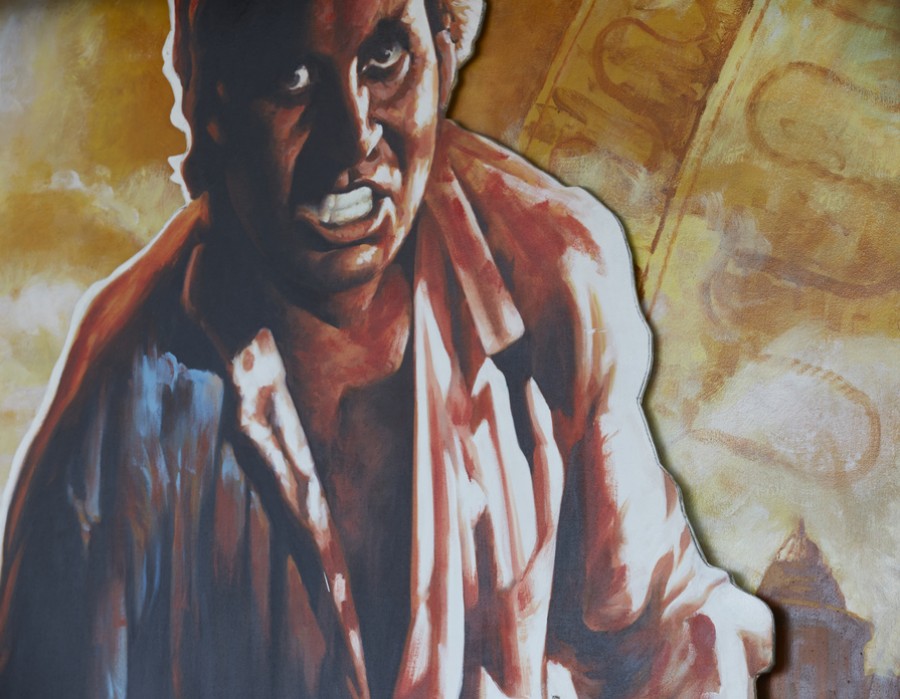

NIMESH PATEL

Nimesh Patel draws on his skill in portraiture to portray one of Bollywood’s icons – actor Amitabh Bachchan. The ‘angry young man’ of 1970 Bollywood films, is the Bachchan persona most identify with. Here, Patel chooses a stance from Deewar, one of Bachchan’s most popular films,that shot him to super stardom and left most young actors (and non actors), aspiring to be angry young rebels without a cause.

Drawing on this star aura, he playfully casts his mise-en-scene. “In this particular work I have created a fictitious machine—a magic box- where different individuals walk into the machine and come out as Amitabh Bachchan,"said Patel. The specific image that Patel has chosen from Deewar, is that of a street-smart Bachchan standing with his arms akimbo, his sleeves rolled up, shirt tied in a knot and a dockyard worker’s badge strapped to his arm, referencing the actor’s role as a revolutionary hero.

The idea behind using the iconic figure is actually a critique of the tendency to idolize people and the homogenisation of aspirations and ideology. "No matter how much you try to suppress individual ideology and create clones of an icon, one cannot be successful in that attempt. People will rise up in revolt," argues Patel, echoing George Orwell’s epic novel 1984, which critiqued the Communist ideology of enforcing similitude and wiping out individualism.

While conceptualising the work, Patel decided to combine poster art with kinetic elements. Patel began with a large canvas work to simulate the actual mechanism; the box and the moving figures are articulated in a manner where they appear three-dimensional despite being merely two-dimensional painted forms. The second level of the work involved painting the figures directly onto the conveyer belt so that they actually move towards the ‘magic box’ that morphs them into Amitabh Bachchan.

BIRDS OF PARADISE

RAJEEV SETHI & BHAJJU SHYAM

“Viewing a good image begets good luck” or so the saying goes among the Gond tribal community who traditionally inhabited the forests of Madhya Pradesh.

Conceptualized and directed by Rajeev Sethi, ‘Birds of Paradise’ reflects his profound belief in the synergy of the traditional and the modern. “I do not accept the polarization of the ancient and the contemporary nor do I subscribeto the hierarchies between artists and craftspersons.” said Sethi, explaining why his animation of Gond paintings for the Mumbai International Airport art program isnot as stark a departure from “tradition” as one might imagine.

For the artwork program at the Mumbai International Airport, Sethi and his teamof designers collaborated with celebrated Gond artist Bhajju Shyam to create animated images ofairplanes depicting various stages of flight in the typical Gond style. The bas-relief spans 36 feet x 6 feet; on it are painted images of fantasticalflying machines, birds and aeroplanes flying over the metropolis of Mumbai. The Gond artists’ innovative interpretations of the mythical udankhatola fuse the forms of airplanes, helicopters, animals, and birds to createfantastical and whimsical flying vehicles.

Many of these ‘mutant’ flying vehicles defy the laws of structure and geometry, giving them an appearance that is more organic than machine- like. They jump and bound over a skyscape of happy clouds and rain patterns, suspended over a cityscape that is made surreal by the sudden presence of a large screaming face of the Bollywood star, Amitabh Bachchan. The entire landscape is an aerial view of a muted land, sea and water scape of browns, greens and blues, throwing the brilliant colours of the Gond’s new age khatolas into stark contrast.

“I love their form and line and I did not want to deviate from that, however I wanted them to push themetaphor for flight and journey and see how they would interpret traditionalmedia and juxtapose it with new media.” says Sethi. He also wanted the relief, crafted in fibreglass by Sher Singh, to simulate the texture and quality of sedimentsandstone and incorporate the striations of sediment visible in unpolished sandstone. Bhajju Shyam painted over this surface followed the direction of these striations as a reference when composing the forms.“Gond painting requires one to see into the essence of an animal, tree or living being,“ he explains. “We aren’t interested in realism, so what was neededwas to capture what is in the mind’s eye, to translate an imagination of whatthese enchanting birds and airplanes were and how they would have behavedwhen in the air. The real novelty, to my mind, was in using Gond idioms as they have never been used before”.

SPIDER WEB

RAJEEV SETHI & RAJESH VANGAD

Conceptualised and directed by eminent scenographer Rajeev Sethi, ‘Spider Web’ presents the story of Dahanu,one of the last green belts left in the state of Maharashtra and the only remaining habitat of the indigenous Warli tribe.

"Conceived as a prism that moves from the jungle to thepastoral village and then to the urban, Spider Web is a kinetic installation that utilises the technology of trivision advertising billboards. Triangular slats placed inside a frame rotate mechanically revealing three individual compositions, each capturing one aspect of the changing way of life among the Warlis as seen through the eyes of the Warli artist Rajesh Vangad” says Sethi.

Sethi and Vangad experimented with unconventional materials to meet the challenges presented by the format, the kinetic nature of the installation and the site conditions. Workshops decided the use of canvas and vitrulan board as the base, these surfaces coated with a mixture of cow dung, mud, glue, and acrylic paints. These were then painstakingly textured with thumb imprints to simulate the characteristic aesthetic and texture created by the artists as they apply mud across the walls of the hut in bold sweeping movements. The motifs are painted in white acrylic paint but the bamboo styli used are entirely traditional.

A river emerged as the central element of the first composition depicting the Warlis’ life as hunter-gatherers inhabiting the jungle. On either bank are lush forests, the entire image, giving testimony to the local biodiversity with all manner of trees, birds, animals and insects depicted. The sizes of the trees vary greatly, a phenomenon new to Warli painting. The Warli gods – Harve (the peacock) and Waghya (the tiger) preside over this idyllic landscape. " Waghya is invoked before we begin any new endeavour or before we beginthe day’s tasks.” Explains Vangad. A large image of a tiger blesse the travellers of the Mumbai Airport and protects them on their journeys.

Each phase of the Warli calendar is detailed in the second composition along with images of the different occupations practiced in the village – the basket maker, metal smith, potter, carpenter, weaver, and spinner all ply their trade.

Painted against a smoggy blue, the city is a bustling concrete jungle of high-rise apartments and office complexes. Amongst these are prominent Mumbai landmarks such as the Taj Hotel, the Gateway of India, and the Mumbai Airport. Buses and automobiles ply the winding streets while airplanes populate cloudy skies.

"Following the Warli tradition of processing the world around them through metaphor, their transition from the jungle where they lived as hunter-gatherers to a farming community that is gradually being ‘urbanised’ is captured in the allegory of the spider-web that underpins this installation,” says Sethi. "Noiseless and patient, the spider launches forth filament by filament out of itself. Tirelessly, it constructs its ingenious home that doubles as storage and egg incubator. Fragile, the web may be rent by the wind or larger animals. And yet, the spider, tenacious as ever, spins another intricate web."

HOPE

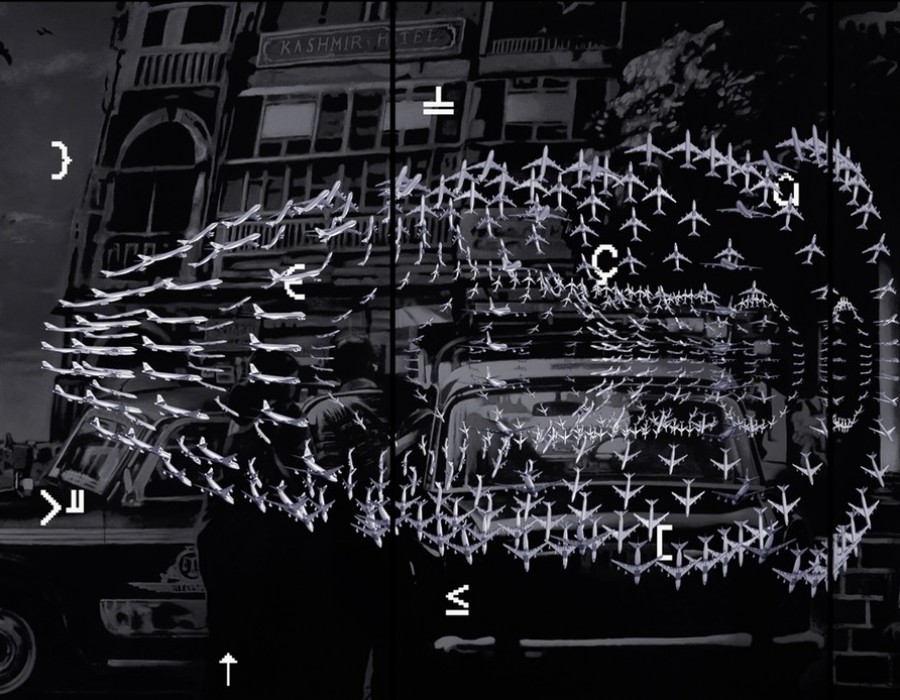

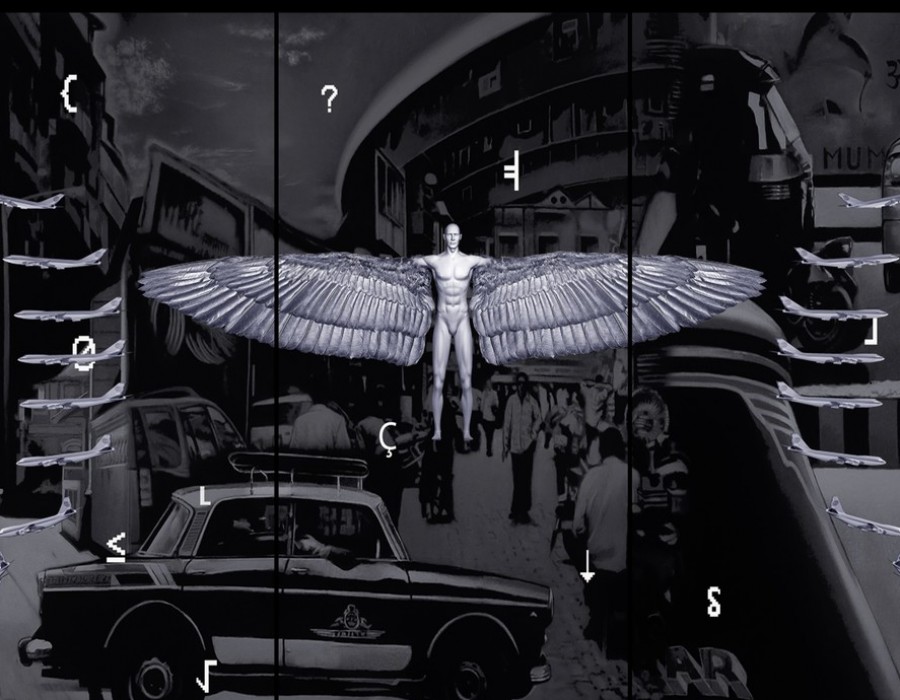

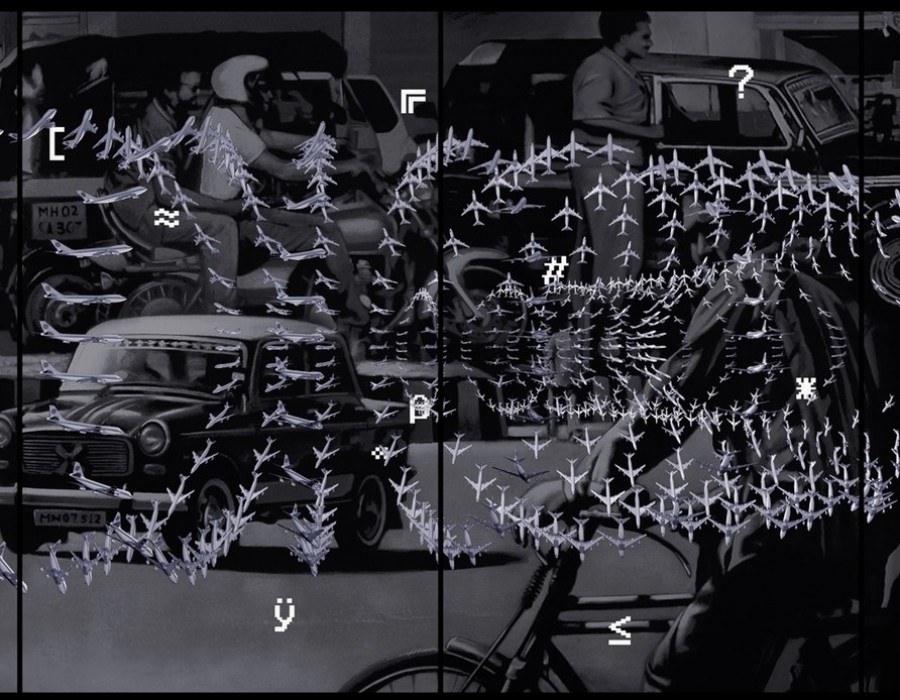

BAIJU PARTHAN

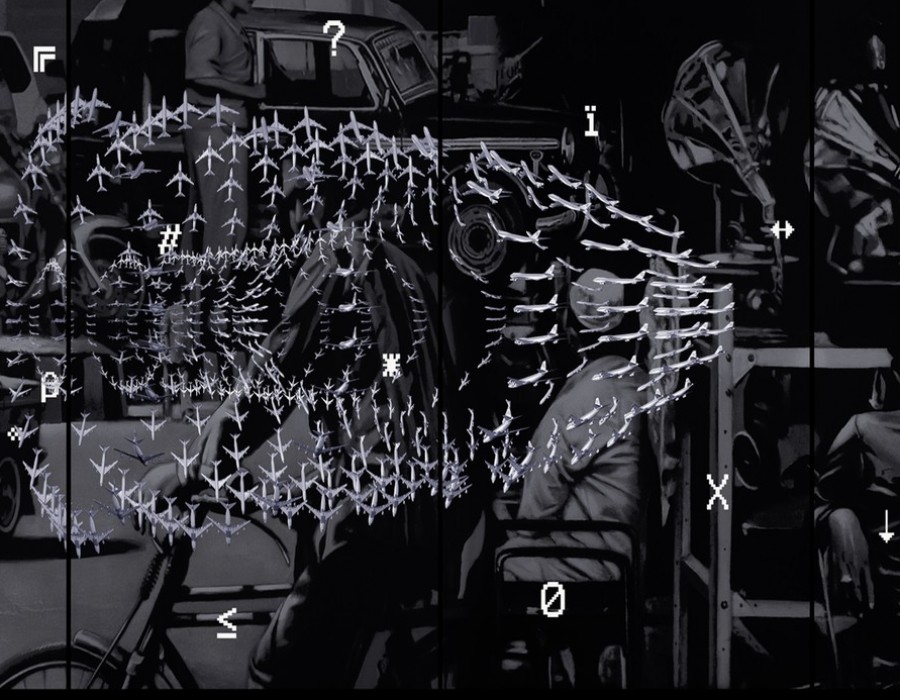

Wait for that 'magical moment' in Baiju Parthan's work; that moment when the image changes from one of taxis and buildings to that of Icarus. On viewing this 36 feet long lenticular print work,one sees the bustling city of Mumbai with its bikers, commuters, Art Deco Buildings and the iconic black-and-yellow Fiat taxi-cabs. As one changes one's position of viewing, the image turns to that of Icarus, an anti-hero from the Greek myth, who dared to aspire to fly.

"As a resident of the city of Bombay I wanted to work with the Fiat taxi because they have mostly vanished from the cityscape, and it's a big loss," says Parthan who has been painting taxi-cabs for quite a while. "For an artist a fleet of Fiat taxis parked in Bombay/Mumbai becomes iconic. It is also part of Bombay's cinema history. I have created a kind of a montage with these taxis and I've overlaid them with new media elements."

His own personal experience of travel outside the country led him to use a mythological element in the work—the image of Icarus. "It is not important that he failed but it's the whole intention of going beyond the given, that attracts me," says Baiju. A journey from the taxi to the aspiration to fly is implicit in the work. "The suggestion of Bombay as a place where one can transcend one's limitations, through opportunities is also underwritten," says Parthan.

He went on to create a scenario where the graphics of the Icarus figure and an egg shaped sphere of jumbo jets that is breaking open. "I chose lenticular prints as the medium because the technology creates the illusion of space and animation," he says. This lenticular mural involves many stages of crafting, testing and careful putting together: painting, overlaid with digital graphics and photography.

To Parthan, photographs are not purely documentary in nature. "Photography is my way of establishing the city in retrospect. Because the city of Bombay/Mumbai is always evolving and there is no 'absolute city' as such. So I've been modifying my photography in context to my experience of contemporary Bombay/Mumbai. I have been layering three-dimension graphics for a while," says Parthan.

REAL BUT ILLUSORY

GANESH SELVARAJ

If you think your eyes are playing tricks on you as you get off your long flight, - circles and dots appear and disappear, as you look at these angled glass panels - then Ganesh Selvaraj has succeeded in drawing you into his work. "It’s this illusion and ‘play’ I am after," says the artist.

Five circles and dots move as you pass the work. Much like a mirage that appears real but is merely a figment of our imagination, the circles can be read as a larger metaphor for life. All that happens is real, yet on the spiritual plane, is it really?

Dwelling on notions like time and infinity, perception and experience, Selvaraj’s works usually employ visual devices such as rays of light that originate at one point and disappear into nothingness, angles that give multiple dimensions to a plane, endless lines conjoining into chaos.

While the work operates on a philosophical level and makes a metaphysical statement, the technical aspects of the work required a solid plan. Thirty feet in length and six feet in height, 4mm thick glass panels sandwich vinyl cut out circles. "Personally, I enjoyed working on this large scale," says Ganesh, even though the weight of the piece made handling it very difficult. He had to direct the work – "it’s not like painting on canvas … you can’t display the whole work and see the composition. We have to install it layer by layer."

Selvaraj has used multiple sheets of 4mm glass between which black circles made in vinyl are sandwiched.Consisting of around 3,000 glass sections, it weighs approximately 8000 kilos. The glass panels have been installed such that they are slanted at 45 degrees – this was to ensure that only a minimum amount of natural light was reflected and the circles and dots are clearly visible.Due to its scale, weight complexity, the work required a tremendous amount of planning during both production and assembly.

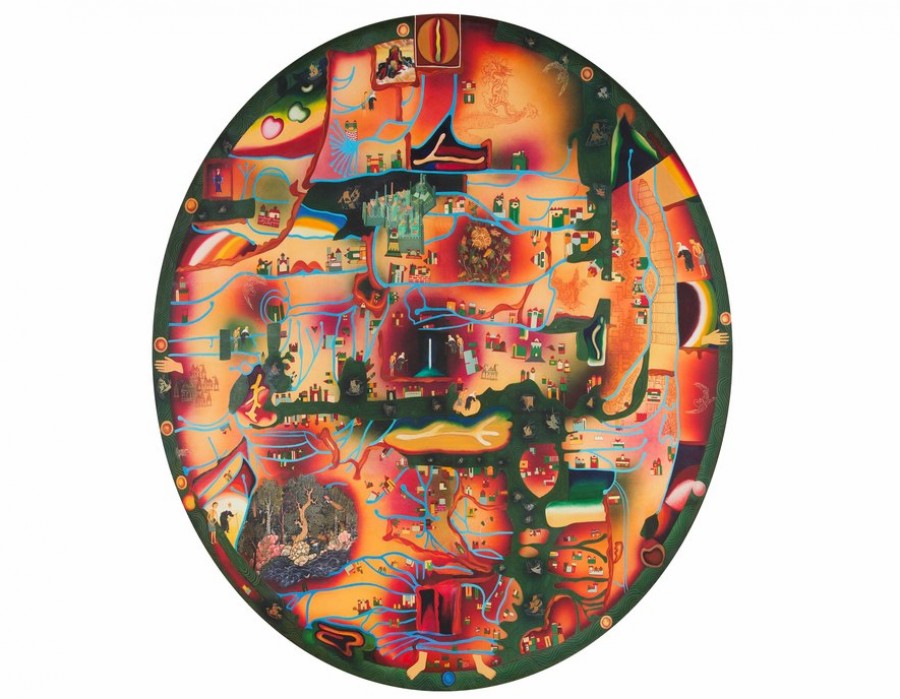

JOURNEY ACROSS TIME

GULAM MOHAMMED SHEIKH

If a painting allows the viewer to enter it, it becomes a mappa mundi. The world opens in different ways, life and art become indistinguishable," says Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, who's 'Journey across Time', evokes journeys both temporal and metaphysical.

"As individuals and as a species, we are constantly journeying," says Sheikh, "through our lives, through eras. Referencing the transient yet cyclical nature of time, the artwork follows the passage of night into day, opening with moonlit clouds, merging into a rose tinted dawn, becoming brighter and brighter until it culminates in the golden hues of the sun."

Within this luminescent landscape are six or seven discs, each a reinterpretation of the mappa mundi or medieval European maps of the world, which were intended not for navigation, but as schematic diagrams illustrating the symmetrical geometries of the known world and the harmonious order of God's creation. "Six-seven hundred years later, it is still possible to dream and to re- envision the world ... using the same structure but playing with it, introducing new images into it." says Shaikh.

Each mappa mundi is an intricately wrought circular world, replete with rivers and oceans, mountains and deserts. Interspersing Buddhist pagodas, Jain cosmic diagrams, the Hazratbal mosque and the Shankaracharya temple, are mundane scenes - workers toil on the construction of a skyscraper, small neighbourhood stores sell their goods, a passerby pauses to drink water.

"In Indian classical music, the cyclic rhythms of the universe are reflected as tala, a recurring time-measure ... I liked the idea of translating this visually ... the discs rotate slowly, returning to their state of rest when the viewer retreats or moves away."

Linking these mappa mundi are a series of heraldic figures. Hanuman, the son of the Hindu God of the Wind, leaps across the skies. Sufi dervishes practicedhikr, arms outstretched to the earth and the heavens. Angels float in dreamlands, Gandhi walks across India, his journey a non-violent path to Independence, the poet-saint

ILLUSIVE DESCENDING

JAGANNATH PANDA

A painted backdrop of light green is swathed in a purplish, yellow fog from which emerges Mumbai's skyline as a shadowy skeletal outline of buildings. Against this backdrop are trees covered in printed silk, a visual homage to the textile industry that formed the economic backbone of the city.

These nine panels covered with canvas, 36 feet long and 6.5 feet high work are the work of Delhi based artist, Jagannath Panda. "I found that trees were a recurring motif in my work, a visual reminder of the constant push and pull between development and the disappearing forest land," says Panda.

"Because I was creating the work for the Mumbai airport I decided to factor in the migration of thousands of people into this city of aspirations," says Panda, whose team of assistants, include migrants from his hometown in Orissa. The trees are a metaphor for these intrepid souls - the migrants; their branches reaching for the skies while their roots provide a stable anchor, tapping into hidden strengths and desires. "This urban development often comes at the cost of an imbalance of our ecology and a loss of forests. For me Mumbai is a microcosm of what is happening in India."

Dwarfed by this mystical woodland are iconic high rise buildings and apartments, bands of men carrying idols of Ganesh, statues of the Maratha warrior Shivaji, that populate the city's roundabouts, couples sitting by the shore, vendors and film stars... each a visual homage to Mumbai. Above them, soar bizarre flying locomotives, contemporary interpretations, of the vehicles described in epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata.

MUMBAI ONCE BOMBAY

LALIT SHARMA AND KAPIL SHARMA

Father and son, team up in an unusual inter-generational and inter-disciplinary collaboration. Lalit Sharma, a traditional miniature painter trained in the Nathdwara style and his son, Kapil Sharma, a graphic artist, work together on ‘Mumbai once Bombay’. Fusing miniature painting and graphic design, the duo began an artistic dialogue, during which delicate brushwork of the Nathdwara school and its jewel-like colour palette encountered digitally rendered images, typography, street photography, and architectural drawings."What we wanted to highlight in this project is the difference in the worldview of each generation and the manner in which it is expressed. My father is a practicing contemporary miniature artist, while I am a graphic designer. We thought it would be interesting to combine both aspects and skills, to effect a symbiosis of the old and the new," explains Sharma.

By focusing on the changing architecture of the city, the work reveals a sort of timeline of its shifting aesthetic. Images chosen are important landmarks of the urban landscape of Mumbai – the Ban Ganga area, the Bandra-Worli Sea Link, the Taj Hotel, the Gateway of India, temples, high-rises, the sea, twisting flyovers and a scattering of coconut trees.Employing windows as a storytelling device, a number of smaller narratives of everyday life will be noticed on repeated viewing. The frames as entry points into the multicultural fabric of Mumbai bring the various communities of the city into focus – the Parsis, the Koli fishermen and their goddess Mumba Devi who seems to have disappeared from the contemporary cultural landscape."

The miniature painting style is also referenced in the simultaneous use of multiple perspectives."We had to play with multiple perspectives, incorporating the view from up on high and the eye level of the street we used the technique of miniature painting that combines different perspectives on a flat plain, but substituted the drawings for photography

TINACITY

MEERA DEVIDAYAL

"For many years now I have been driven to the point of obsession with the idea of the migrant and the dream city,it’s about someone who enters the city while treading the razor’s edge between the dream he/she has to fulfill and the reality, so it’s this negotiation of the neon-lit welcome of the city and the swampy underbelly"says the artist.

As one comes in to land in Mumbai, the informal city of irregular construction sits cheek by jowl with the shiny new towers that arise amidst the tarpaulin clad corrugate sheets.

Artist MeeraDevidayal’s installation along the travelator, reflects on exactly this dichotomy, of decay and renewal, of hope and aspiration. Contrasting with the plush surrounds of the new terminal building, she brings the other co-existing world in – in a very tactile way, the material of the work is the very same humble material used by millions of inhabitants of the city.

"The idea to work with metal sheets happened when I went to someone’s home in a slum. It could have been and average middle class house; the only thing was that it was in a tin shed."An unconventional material, it was difficult to plan the work on a drawing or a computer. Every sheet had its own character and Meera had to work with each sheet individually to create this tribute to the tenacity that motivates people to manage life in a city that threatens to overwhelm them in so many ways.

Devidayal has always drawn inspiration for her work from the popular culture of the city. As is seen here – from taxi-walas to zari workers, daily wage labourers to domestic workers – their wayof habitation is highlighted. She often juxtaposes the harsh realities of this working class milieu with the aspirational glamorous world of Bollywood.

This work is anchored in the narrative of the migrant worker in search of his dreams in the celluloid lure of Mumbai.

TRANSIT II

MITHU SEN

"There is something bitter-sweet about journeys; it is the excitement of arriving at a new destination and the sadness of leaving behind an old one."

One gets a sense of this duality in the forlorn rows of suitcases that are in the foreground in one of the panels a metaphor for the past that we constantly carry around in our hearts and minds.

"It is not just the physical journey that I allude to in these works but also a metaphoric journey that is continuous. Movement is central to life; if the heart stops moving, one dies,"says Sen.

Here, a large installation, 40 feet x 6 feet in size is devised as a series of ‘light boxes’ within which the artist has embedded multiple layers of painted, drawn and collaged images either worked directly on or sandwiched between two layers of handmade Kozo paper imported from Japan.

"Over the Kozo papers, I have drawn other imagery that is inspired by the theme of journeys, migrations, and flights. I have culled these images from my repository of childhood memories,” says Sen.“As adults we envision what lies ahead but very often that is dictated by flashbacks to our past."

Although none of the images used reference the city of Mumbai directly, they allude to the nature of migration, displacement, and travel that is both necessary and disconcerting, all suggest journeys both surreal and contemporary. Images of old family homes in left behind villages to industrial chimneys in the big city, a bicycle, birds of fantasy, uprooted trees and suitcases abound – all seem the landscape of transit.

"I believe art is a living thing and one must consume it with other ‘stuff’ like announcements of delayed flights, bad espresso coffee, slightly stale airport food and the general chatter of fellow travellers.

MULTILAYERED CONURBATION

SAMIT DAS

Delhi based artist Samit Das has seen his home city grow concentrically outwards-the conurbation of expanding cities as they subsume and absorb smaller towns that are reached by this growth. This conurbation is intensified in Mumbai, the main city bound by water, the density has remained more contained but yet, not constrained.

In the artwork commissioned by the Mumbai International Airport, Das juxtaposes the historical images of Mumbai with the contemporary; the juxtaposition and tension between different styles of architecture embodying the meeting of Mumbai’s past and its present life.

This installation of eight panels spans 32 feet in width and 7 feet in height. Drawing on the data he painstakingly collected on the city, Das has been building a layered assemblage, a structure he describes as "a series of spaces-within-spaces, taking the viewer on a journey." Leading visitors beyond the surface, the layering is symptomatic of the complexity manifested in every nook and cranny of the city. "One could say this is true for most of India but it is more palpable in a city like Mumbai that is founded on diversity. Even though this work is just a drop in the ocean, it is a microcosm of the city."

The first and most conventional of these layers is acrylic on canvas, with edifices rendered in broad bold strokes in black against the pristine, white coated canvas. With each subsequent layer, Das adds intimacy and textures to the city. The second layer consists of laser engravings on acrylic sheet; the third, laser engravings on board. By using laser engraving, a technique routinely used by the fashion industry, Das references the spirit of Mumbai, a city driven by glamour and fashion. The fourth layer utilizes engravings worked upon pinewood recycled from the packing used for heavy tools and machines.

"I am using hand held machines rather than automated machines"

BUDDHIST PITCH

RIYAS KOMU

"I've looked at Sachin as a metaphor- a defender both on the pitch and off, a fellow youngster who has done much more for us by way of unifying the country in celebration and instilling a sense of pride and identity in us. In many respects, this work is a tribute to a living legend befitting, given this is the year Sachin retired and that he is from Bombay."

So says Riyas Komu of Sachin Tendulkar, the cricketer who is a living God to millions of cricket fans across the country. In this work, a homage to the cricketer and cricket itself, a sport that is an addiction in this country, Komu spins the cricket ball, not so much on a pitch but like Buddhist prayer wheels, to be spun reverentially as one passes by. Rather apt, the reference to sport as religion.

"After India won the World Cup in 1983", says Komu, "the whole approach to the game changed. It became part of our blood, inciting a sense of nationalism and unifying a diverse people. It penetrated into every nook and cranny of the country."

The work consists of a series of slim wooden pillars alternating with steel rods on which cricket balls are skewered. Behind this screen-like layer, embedded 4-5 inch inside the wall, are a number of lenticular prints that unify the entire length of the installation.

On closer inspection, it becomes evident that the pillars are modeled on prayer wheels and are carved with symbols taken from Buddhist art and references to similar contexts such as Ambedkar's teachings. "It was fascinating to research Tibetan prayer wheels, Buddhist ideologies and the influences the spiritual tradition had throughout the subcontinent especially in terms of eradicating class and caste consciousness and unifying peoples. In this respect, cricket and Buddhism are alike - that's why I decided to combine the two."

The imagery on the lenticular prints fitted at the back of this layer include fluttering national flags, such as those waved by fans at the stadium; the image is constructed in five layers. Also included are photographic renditions of Tendulkar gazing at the viewer.

"Most people believe Sachin is the god of cricket. I always read Sachin as a political icon rather than a cricketing idol. The initial years when Sachin came to the crease and those of his progression run parallel to the economic and liberal growth of the nation. At the same time, he had his own mission you can see that reflected in his eyes, a determination to play and to succeed. As I kept looking at articles on Sachin, I realised that a sense of national pride.

A WOUNDED SONG FOR MY COUNTRY

G.R. IRANNA

"The concept is always the most difficult part of starting any project" says Iranna. "Mumbai is a unique city, with a different sense of pace, a history of change, even a smell that its own. It is a city of survival and dreams." From a number of ideas bouncing round in his head, two stayed, the memory of the Haji Ali visit, and the history of the city's textile industry, the textile mills and the worker's strikes, an industry that helped build Mumbai and a socio-political movement that shook its very foundations."

"I came up with a couple of concepts. One referenced the qawwals of Haji Ali and the other was based on a previous work in which I had used the motif of the charkhas as a symbol of the labour of the mill workers. I wanted to unite the cultural concept of the mill workers with that of the qawwals... one symbolises a time that has passed, of mills that have been abandoned and demolished to be replaced by shiny malls, while the other concept represents a tradition that has stood the test of time."

Painting the performing qawwals in a photorealist manner, the charkhas were included as a kinetic element in the upper register of the painting. Iranna painted the qawwals as life size figures on a flat picture plane against a sepia toned backdrop, evocative of old black and white photographs, to create an air of mystery and thoughtfulness.

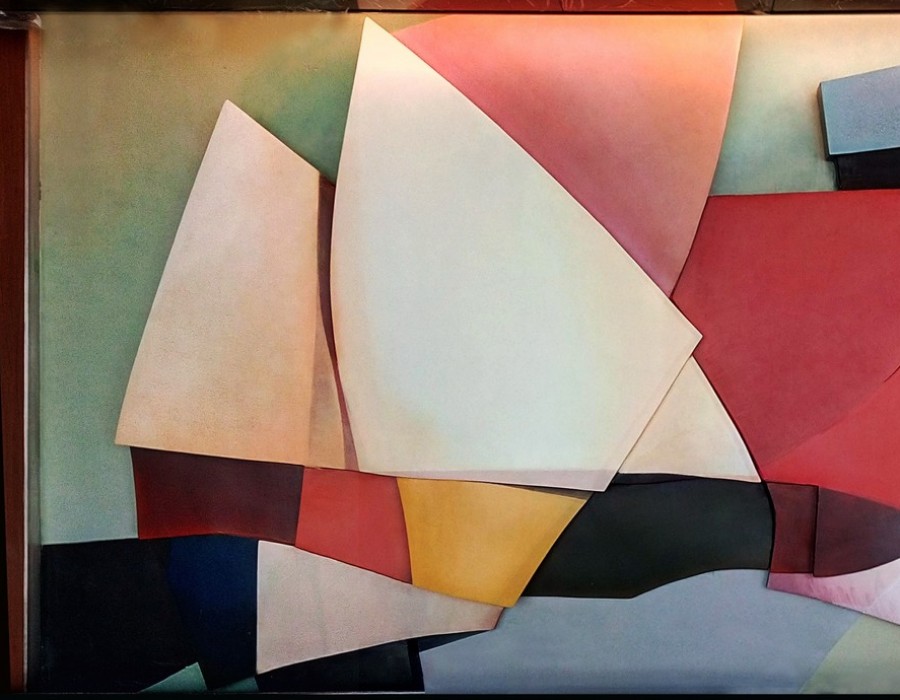

MEMORY BOXES

BHUPENDRA SINGH UPRARIYA

"My work lies between the worlds of the figurative and the abstract,"says Bhupendra Singh Uprariya. "As an artist I can choose to work with a realistic interpretation or to interpret the city in a more abstract manner. I chose the latter."

Presenting Mumbai as a series of abstracted, intuitively created forms, he conjures fragments of the city glimpsed through a passing vehicle - fleeting visions that imprint themselves on one's memory, often in manners that contradict reality.

Uprariya has created a three–dimensional grid of "memory boxes" over an area approximately 6 feet x 4 feet. Made of acrylic, each box is 'injected' with abstracted forms, each representing a glimpsed fragment of the city of Mumbai, familiar known associations of the city - the bustle of its streets, the rattle of the trains, the colours of the sea, the aging cement facades of its buildings or birds in flight. For newcomers, the images may allow for free associations with their own memories or open windows to new experiences.

Individually hand-painted, these forms are rendered in transparent electric blues, diffused greys, bold blacks, and dusty browns and reds on OHP (overhead projector) transparencies. Crumpled and distorted into various shapes, the strips of OHP transparencies convey the manner in which we humans process memories - recalling them partially, blurring out swathes of timewhile focusing on a few scant details subconsciously altering them to fit into larger narratives we find more palatable, and finally, fossilizing them.

"To my mind, Mumbai cannot be captured by a few chosen words or images," says Uprariya. As in the dabbawala's entrepreneurial spirit whose enterprise has elevated the simple tiffin carrier service into a phenomenon - for some it may just remain ordinary tiffin boxes being delivered. Or a villager honed on Bollywood film imagery of the city from a particular decade in his youth, may years later arrive carrying those imprinted images.

CELEBRATION

MANU PAREKH

Working, in collaboration with the Indore based artist Jeetendra Vyas, Manu Parekh's bas relief installation swirls with colour. Featuring abstractions of plants and animal forms, symbols of different faiths, and spaces of negotiation between humans and nature in pulsating reds, placid blues and deep browns, it encompasses Parekh's oevre.

It’s a lively work not weighed down by the problems of the city, rather a celebration of its energy and cosmopolitanism. "This is not a contemplative work, involving intricate forms of a heavy narrative that is intellectually stimulating," he says. If one does get off the travellator, one would be rewarded with sensuous details like the stop-motion blooming of a lotus flower in the moonlight, or the explosive red energy of the Gulmohar flower in the monsoon, placed outside the temple as the horizon is crisscrossed by telephone wires.

"Flowers are central to my work for they are present at all our ceremonies, whether it is birth, marriage or death. They symbolize procreation, life and beauty. India is a vibrant, colourful country of festivals ranging from Diwali and Id to Christmas - it is this festivity that I have tried to capture here."

Parekh has always worked on conventional two-dimensional surfaces such as canvas and paper until this commission. "Frank Stella's murals have always inspired me and it his sculptural approach to two-dimensional work that I have taken my insight from." A fibre-glass relief was painted over, then mounted on six panels of stretched canvas and rice paper, all moulded into one unit.Mumbai is a microcosm of life in a metropolis where a diversity of faiths, creatures, ethnicities and economic classes not only just co-exist, but fundamentally create the city's very fabric. I have tried to capture this by the close juxtaposition of religious symbols... the spire of a church, the dome and open arches of a Mandir (temple), the crescent moon of a mosque and fertility symbols like the flaming red linga (phallus) contained by the calming influence of the yoni (vagina) symbols that also seen as the life giving forces of nature," says Parekh.

A TRIBUTE TO SOAK

ERIC SAKELLAROPOULOS with RAJEEV SETHI

A Seminalexhibition of Mumbai as an estuary was curated by architects Anuradha & Dilip Da Cunha. The very site of the airport with the choked Mithi River is reflected in this work. Deconstructed and transfigured into a dynamic inlay made with a varity of woods disappearing in the jungles, Mumbai's transformation as a megapolis in 1930's is superimposed with art deco motify providing a provocative interface.

THE URBAN PRISM

RAJEEV SETHI SCENOGRAPHERS

SALAAM MUMBAI

RAJEEV SETHI SCENOGRAPHERS

Mr. Sethi has worked with ordinary photos with the british artist Blue Logan to celebrate the spirit of those who will one day own the city.

SEVEN ISLANDS IN THE SEA OF HOPE

PAPRI BOSE

BIRDS AND SHIPS

JITENDRA VYAS

METROPOLIS

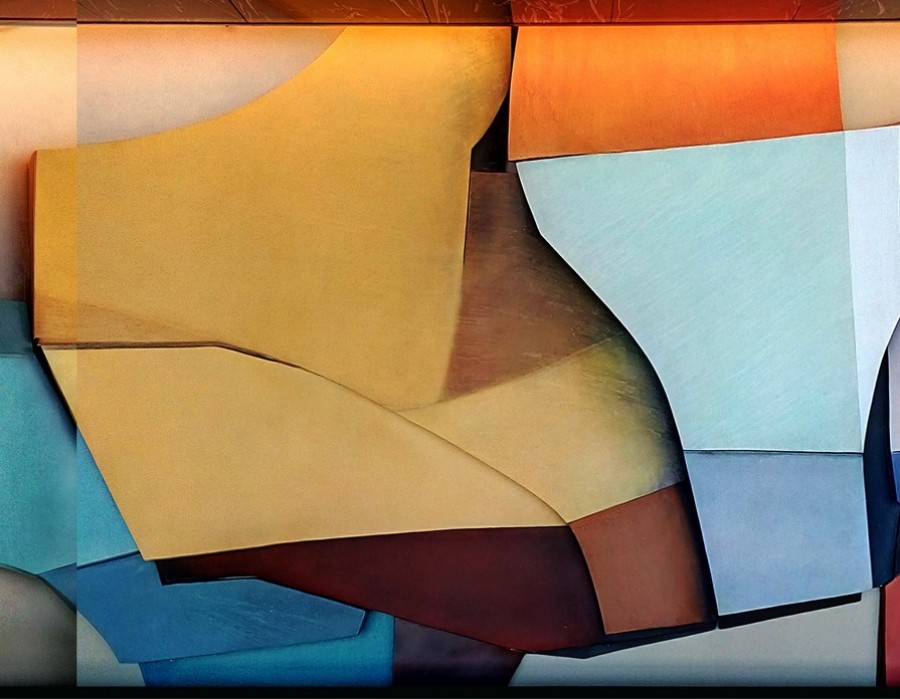

AMITAVA DAS

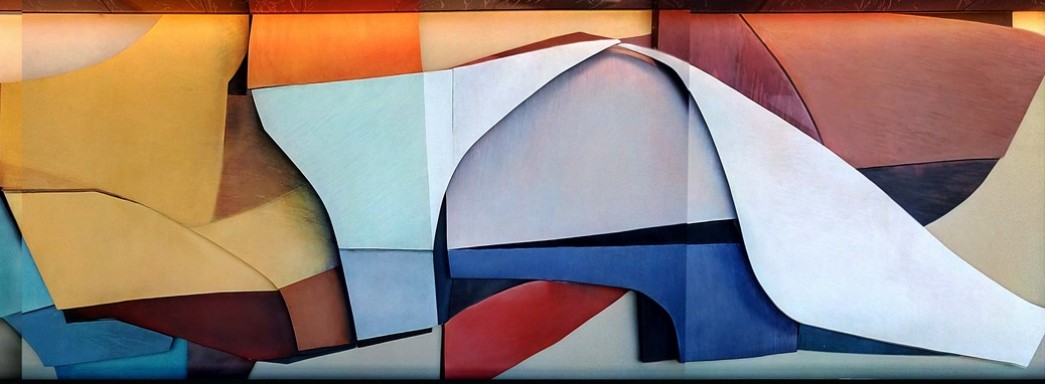

Amitava Das is not a storyteller - "my work is not narrative or topical". He bases his work 'Metropolis' on a generic city and not just Mumbai. "Like any metropolis, it has many spatial divisions and varied communities, is filled with movement and pauses, conflicts and co-existence. I wanted to combine the drive towards 'progress' and 'growth' with the complex phenomenon born of this transformation,"says Das.

Using a formal approach and his signature geometric forms and clusters of thick dark lines, he presents an aerial view of the city. On this colour-infused background, large stylized human forms, which dwarf the grid, are juxtaposed.For Das the human figure is primary:"A city without a man is not a city, it only grows with human beings, it is a jungle otherwise."

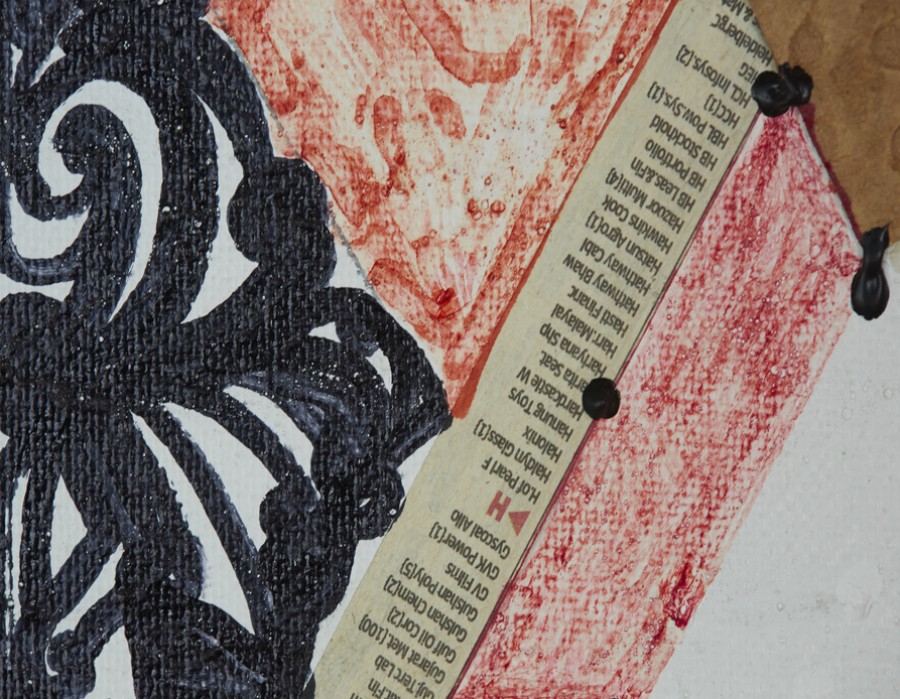

Within this formalist approach, LED lights are inserted into the canvas at nodal points. Glowing, like the soft lights of the city that greet a visitor as a plane comes into land into this teeming metropolis, they soften the hard edges for a moment. They flicker, emulating a city's heartbeat - the promise of life in its towers and industries await. Pasted onto the canvas with 3M, permanent glue or staples, are small pieces of paper taken from the Economic Times that hint at the monetary concerns that underscore city life, while another cutting from a craft based organisation’s visiting card – "Thank you for helping us in keeping our craft and heritage alive" – appears to be a nod of approval at the curation that has driven Mumbai airport's Art Program The entire work consists of eleven canvases. Mounted on panels, viewed from the travelator, one experiences the city - as a series of tensions and ruptures, presences and absences. Angled at gradients, the compositions take on an architectural quality. None of the forms are representative though of the urban jungle depicted, as Das wants no obvious statements but "the works to be experienced in a purely retinal manner as the viewer engages with the aesthetics of colour and form. As the forms appear and disappear, some will slip into the viewer’s subconscious, reappearing loaded with unexpected meanings."