WALKING TOWARDS BOARDING GATES. 43 & 44

Dwelling on the idea of tradition and transition as a cultural continuity, ‘India Seamless’ creates visual connections between temporally and geographically disparate Indias. Thus, history, living myths and popular perceptions are jumbled together to showcase India’s changing vocabulary of architecture and design elements in all their diversity across regions, climates and communities.

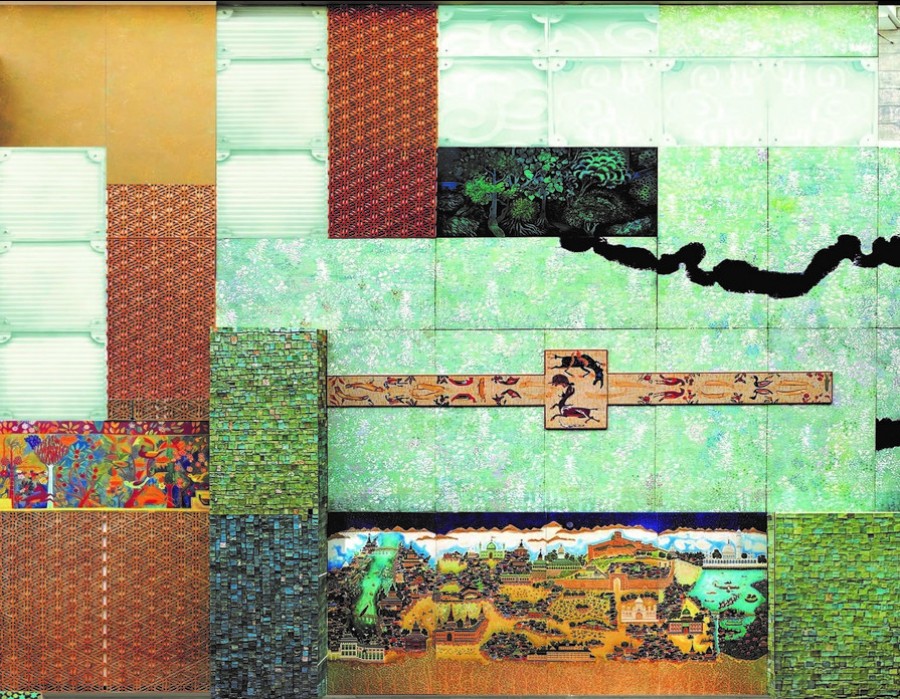

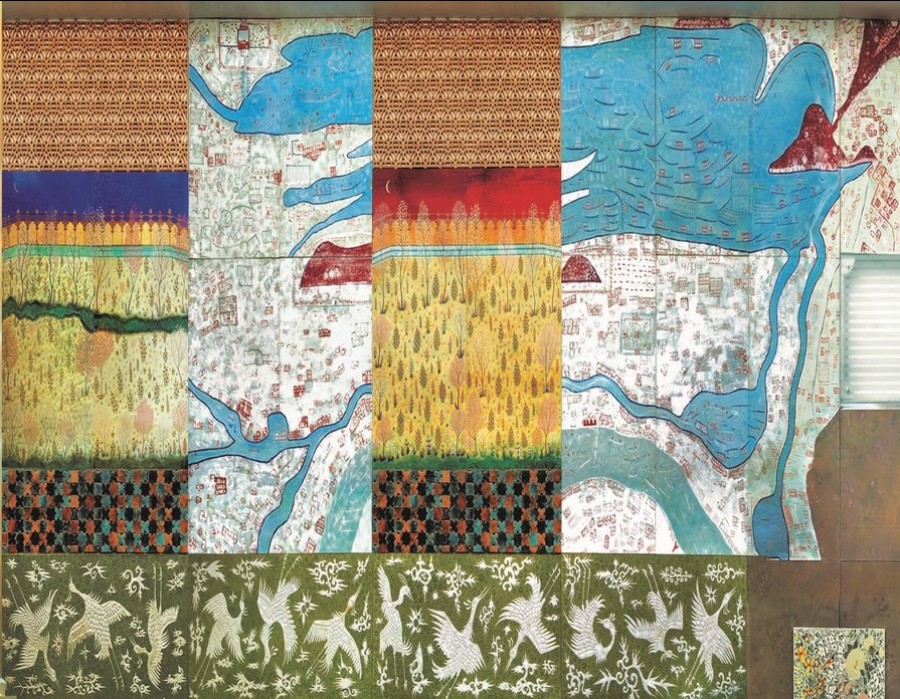

This section was conceptualised as four talismanic panoramas, each an artistic rendition of the four regions of India – the north, south, east and west. When seen together, they become one, the story of India. These works through the creative collaborations between artists, designers and traditional craftspeople position cultural artefacts and legacy skills with the contemporary.

CONJOINING LANDS

NILIMA SHEIKH AND B V SURESH

Trained as a historian before she trained as a painter, Nilima Sheikh delved into the history of Kashmir, tracing the trajectories of its turbulent landscape. In keeping with the theme, Sheikh and BV Suresh, another veteran artist from Vadodara, conceptualised ‘Conjoining Lands’ as an imaginary world of symbolic landscapes that speak to cultural synthesis rather than geographic or political boundaries.

‘Conjoining Lands’ isn’t about creating a utopian world. The very premise of a utopia suggests the presence of a polarised opposite, reality... It does not present Kashmir from a fixed point of view, or place it within our personal narratives as we would in our own work. Instead, we have tried to represent multiple ways of constructing history, geographies, time, and space through different media. Visual references from the region’s art history serve as reinforcements, drawing links between Central Asia and South Asia, hoping to throw open boundaries,” says Sheikh, including in the work, sections of a painted panel that quote Kashmir’s Persian antecedents. “Though Suresh and I have conceived the entire project, our intention is to make the work extend into a collaborative effort. So there are the canvases we created with many young artists at the painting workshop in our studio in Vadodara – Mahesh Baliga, Prasad KP, Chandrashekar Koteshwar, Sudip Dutta, Rashmimala, Raju Patel, Jayanth M and Sharath K. Sasidharan Nair, a senior artist and teacher at the Faculty of Fine Arts, is creating the glass sections, while Nehal Rachh worked on the ceramic elements” says Sheikh.

Choosing to work closely with indigenous crafts people from Srinagar “because in addition to what crafts may be used to articulate in terms of the composition itself, they also tell their own stories of continuities and ruptures,” says Shaikh. “It seemed befitting considering our composition was inspired by a late 19th century shawl we saw in the collection of the Srinagar Museum. Adds Suresh, “The embroidery of the shawl represents a birds-eye view of Srinagar with its main street buildings and gardens. There are even tiny boats on the Dal Lake and the River Jhelum.”

“We eventually narrowed down to crafts associated mainly with wood,” explains Sheikh. “So we included two distinct woodwork techniques of Kashmir – the pinjrakari lattice screens and the geometric patterned khatamband panels, which were custom-made for the installation by Shakeel Ahmad Najar& Associates and Mohammad Yousuf Najar & Associates respectively,” says Sheikh. Sheikh and Suresh also decided to include the crafted houseboats, commissioning Nazir Ahmad Muran, renowned for the houseboats he constructs from deodar.

In addition a combination of the conventional papier-mâché technique and relief work or ubhrakaamis used to create three dimensional, ‘embossed’ forms on a flat surface. “The change in dimension changes the experience of the work, especially at this scale,” says Sheikh.Looking at creating a synthesis of elements and materials, the work attempts to destroy hierarchical perceptions of ‘art’, ‘craft’ and ‘architecture’.

“One of the challenges we faced when we were conceptualizing the work based on the shawl map, and references from historic paintings, was the shift in scale. Miniaturisation, as a representation tactic, allows ‘reality’ to be filtered through artistry. Here we were working in reverse, using the pictorial language of the miniatures as a language, but dramatically altering the gestalt,” says Sheikh.

Walnut wood - carving

Walnut wood carving reached Kashmir from Central Asia 600-700 years ago, through the Sufi Saint Shah Hamdan, whose era is synonymous with peace, progress and prosperity. Kashmir is the only region in India bestowed with the presence of the majestic Walnut Trees; hence Walnut wood carving is among the most important crafts of Kashmir. Wood used for carving can be from the root or trunk of the tree. The wood derived from the root is almost black with the grain more pronounced than the wood from the trunk, which is lighter in color. It is the dark part of wood, which is best for carving as it is strong; it is also among the most expensive.

The carving of furniture and smaller items is an elaborate process and involves a high degree of skill and craftsmanship. The Kashmir craftsman rejoices in carving intricate and varied designs, he first etches the basic pattern on to the wood and then removes the unwanted areas with the help of chisels and a wooden mallet, creating an overall effect which tends towards three-dimensional depiction of various motifs or scenes, depending on the number of layers.

The motifs on the wooden artifacts are inspired from the various natural wonders of Kashmir, Chinar leaves, Vine leaves, flowers like Lotus and Rose. The craft was initially restricted to the creation of elaborate palaces, intricately carved buildings, shrines and mausoleums. A single piece can take from 2 days to 6 months depending on the intricacy of the pattern.

Walnut wood has an inherent sheen which surfaces on its own when polished with wax or lacquer.