WALKING TOWARDS GATE NO. 86 & 87

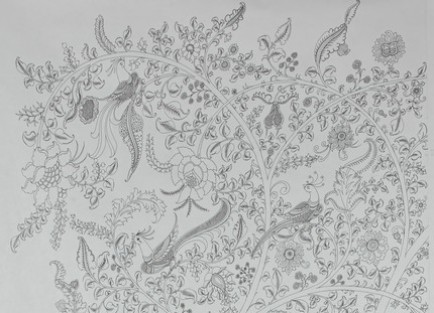

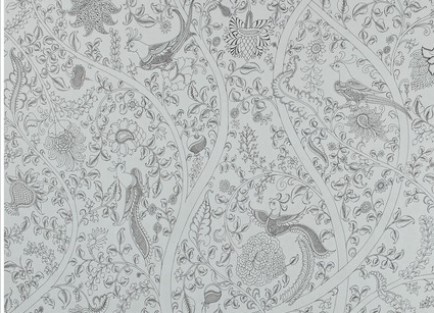

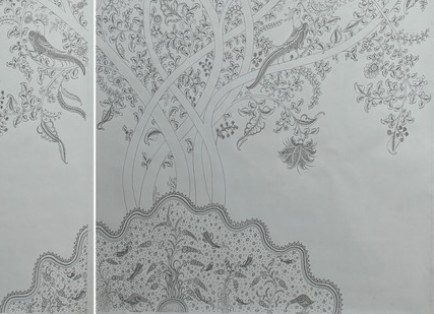

Long before the age of globalisation and the internet, India was an axial point for international trade through which the East-West commerce in aromatics, spices, textiles, and other luxuries passed. This position allowed for not just the creation of wealthy economies and trade networks but also for active exchanges of ideologies, artistic traditions, traditional knowledge systems and practices.

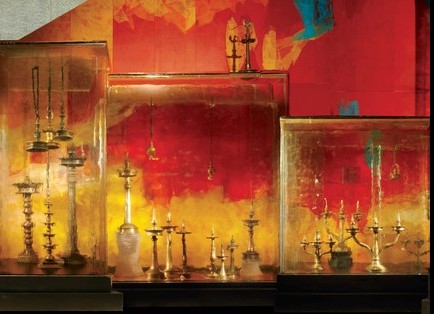

‘India Global’ represents an India, especially post Independence, where new forms, materials, ideas and ways of being coalesce, the old and new coexisting side by side, sparring with one another and more often than not, erupting into fantastic hybrids, at once global and local.

In this dialogue, cities become an important stage where a vast human drama constantly unfolds, constantly in a state of flux, adapting to innumerable forces influencing its act. ‘India Global’ is conceptualised as a window that opens for the visitor to access this humanscape within the urban landscape.